Inventors since the beginning of motoring have been

striving to discover some means of varying the gear between the driving and the

driven members in a motor car automatically and in an infinite number of

different ratios. Theoretically, the perfect gear is that which maintains the

engine's speed constant while it adjusts the relative speed of the road wheels

to all variations in the load placed on the vehicle. Thus on a hill the perfect,

infinitely variable gear would gradually lower the gear ratio as the steepness

of the hill increased and would, therefore, allow the car to move more and more

slowly while permitting the engine to turn at exactly the same rate all the

time.

The ordinary gear-box is a compromise, offering perhaps four fixed ratios and relying upon the flexibility of the engine to span the gaps between the optimum engine speed for one gear and the next. Infinitely variable gears have been invented from time to time, the Constantinesco (q.v. torque converter being one which was successfully tried in a car. Others have depended upon friction (see Friction Drive), that used on the early G.W.K. light cars being an example. In this form of drive an infinite variety of ratios is possible between neutral and top gear, but in practice the gear-changing lever is moved a set distance between one ratio and the next.

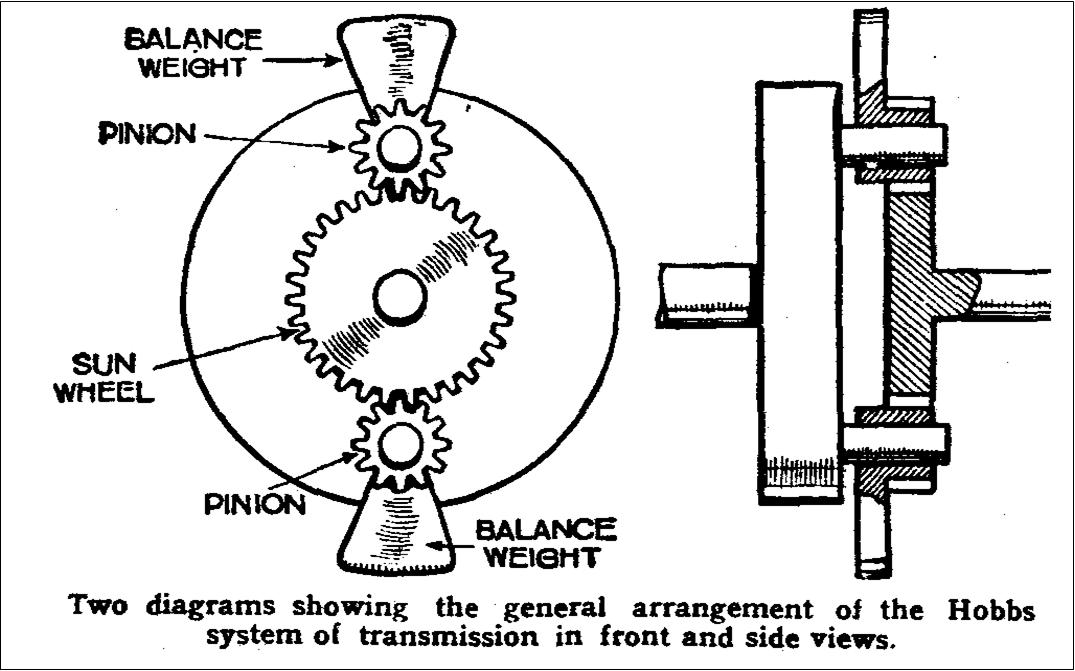

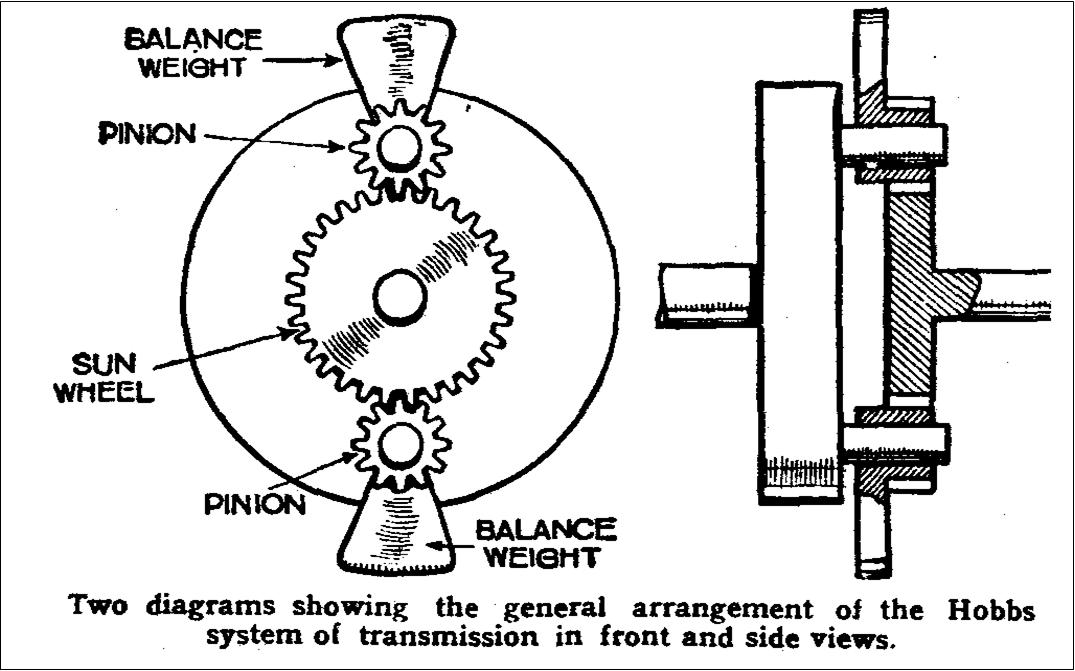

Nearly all mechanical infinitely variable gears, as distinct from those depending on friction, employ some form of ratchet, though it is very often called by a different name. Among the most interesting mechanical infinitely variable gears is the Hobbs " gearlesa " transmission. The essential element of this transmission is an epicyclic train consisting of a disk carrying two planet wheels on each of which there is an eccentric weight, throwing the planet wheel markedly out of balance. Meshing with the planet wheels is a sun wheel keyed to a shaft fitted to the forward end of a long laminated spring shaft. This spring shaft, together with a roller clutch of special type, takes the place of what, in other types of infinitely variable gears, would be the ratchet, or " mechanical valve." In other words it smooths out the drive and converts it from a series of impulses to a steady flow.

The action of the gear is mainly the result of the unbalanced forces set up when the two planet wheels with their eccentric weights are rotated on their disk by the engine. It is clear that the weights will tend all the time to fly out, and that if the disk were turned fast enough, the weights would, under the influence of centrifugal force, remain out and would prevent the planet wheels from turning at all. This condition, being the simplest, may be considered first. Imagine the disk mounted on the engine and carrying its two planet wheels with their eccentric weights. Imagine that the engine is started and that the disk rotates and that a slight braking effect is placed upon the planet wheels. The planet wheels will then rotate independently as well as with the disk. But as the speed increases, the eccentric weights will tend to fly out with increasing force, and if the planet wheels are still to rotate independently, a much greater braking effect would have to be applied to them. If it is not applied, then the disk will rotate, carrying the planet wheels with it, those planet wheels not rotating independently at all.

If, therefore, the planet wheels were connected with another gear wheel, a sun wheel, for example, the sun wheel would be taken round with them as if the whole assembly were locked together. In this condition the driven shaft keyed to the sun wheel would be rotated at exactly engine speed and a direct drive top gear would result. But supposing now that a braking effect, which might result, for example, if the car were being driven up a hill or being started from rest, were applied to the sun wheel. If it were strong enough it would overcome the centrifugal force acting on the eccentric weights and force the planet wheels to spin independently as well as with the disk. And in so far as the braking effect is increased so will be the speed of the planet wheels. The result is that as the braking effect (or load on the car) increases, the gear will be progressively lowered.

A complication is brought into the operation of the gear by the action of the eccentric weights, which do not move with perfect smoothness, inasmuch as they are moving freely in one direction and under constraint in another. They are balanced one against another, but even that does not entirely smooth out the drive, and therefore behind the sun wheel is introduced a roller type of clutch, which, however, can be controlled by the driver for reversing, and the previously mentioned spring shaft made up of a number of laminations. The drive is transmitted through this clutch and along the shaft, so that all jerkiness is damped out and a smooth turning effort is achieved. This gear has been tried with success in an experimental car and has attracted a great deal of interest from engineers.