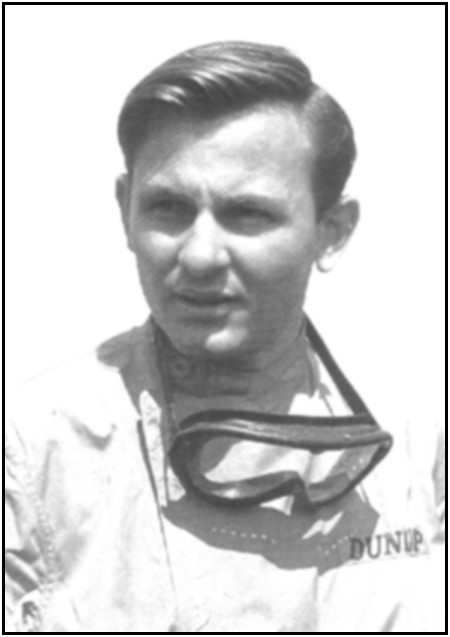

BRUCE McLAREN

Bruce

McLaren's first car arrived as a box of engine bits and a sorry looking rolling

chassis...a couple of years later he entered his first event.

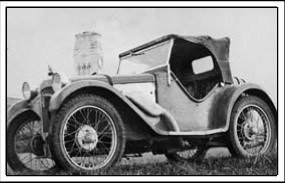

Bruce's automotive awakening came in the form of an Austin Ulster, an open

race version of the ubiquitous and popular Austin Seven. Les McLaren, Bruce's

father and Chairman of the Auckland Car Club, bought the Ulster with the

intention of competing in it in the variety of hill climbs and sand races which

were a major feature of the Kiwi racing scene then. The motor sport community wasn't big in those

days, and everyone knew everyone else. Car swapping was common - both at events

and on a more permanent basis. Herb Gilroy, another amateur racer who was a

member of the Northern Sports Car Club, owned the little Austin in 1946, having

bought it from a schoolmaster who lived in the town of Hastings. When the McLaren clan got the car, most of

the mechanical parts had been removed, prior to a complete rebuild, so it

looked a very sorry sight as it was towed home. Bruce wrote in his memoirs that

he "...eyed the dilapidated Ulster on the end of the rope with deep

suspicion. Racing car indeed!"

It took a year to collect the parts and put the Ulster back together

again. A year when Les, known to the family as Pop, taught his eager son a

great deal about how cars work and what the various bits all did. Eventually

the car was ready and Pop set off on a road test. He came back pale and shaken

and in Bruce's words: "It was the most diabolical racing car he could

imagine. Sure, it went all right, but it wouldn't stop, it wouldn't steer and,

as for the handling...words failed him!" Les wanted to sell the car right

away but Bruce persuaded Pop to hang on to it - in fact give it to him, despite

the fact that he was only 13 years old and still over a year away from his 15th

birthday when he could legally drive in New Zealand.

Once Pop agreed, Bruce turned the family back garden into a miniature

Brands Hatch circuit and spent the next year annoying the neighbours and

learning to drive. "One day,"

he wrote later, "I overcooked it. The gravel patch at the end of the

'circuit' formed a tight right-hand turn between the house and the garage. I

came onto this gravel so fast that even I knew I wasn't going to make it. I

shut my eyes, held my breath and went straight ahead along the side of the

house, missing everything by a coat of paint and coming to a shaken halt. My

first reaction was relief at my masterly evasion of an early demise, but when I

realised what I must have done to avoid the side of the house I was thrilled.

I'd held an opposite lock slide - and told everyone about it for days."

P op was in hospital when Bruce entered his first event, a

op was in hospital when Bruce entered his first event, a  hill climb at

Muriwai Beach, about 25 miles outside Auckland. Hi

hill climb at

Muriwai Beach, about 25 miles outside Auckland. Hi s words of warning to the

youth were short and to the point: if you damage so much as a mudguard, the

Ulster's gone for good!

s words of warning to the

youth were short and to the point: if you damage so much as a mudguard, the

Ulster's gone for good!

Bruce recalls: "This probably did me the world of good, as I was so

busy being scared of bending my car and having it taken from me, that I forgot

to be nervous about my debut. I took things reasonably steadily, with Pop's

lecture in mind, as the tail of the little Ulster slid on the loose metal

corners and reached the top in one piece. When all the runs were over, I

learned with amazement that I had made fastest time in the 750cc

class." It was a magic moment for

the youngster and his affection for the Austin Ulster remained constant. He

recalls in his memoirs how he learned at what he calls "a comparatively

safe speed" what happens to a car when it begins to slide and how to deal

with it when it does. He also learned the importance of painstaking maintenance

and car preparation and how it can mean the difference between victory and

failing to finish.

All the while Bruce was learning and becoming ever more capable

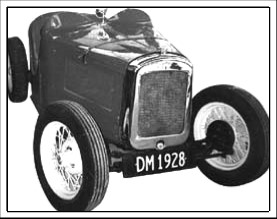

mechanically. In 1954 the cylinder head on the Ulster cracked. He cannibalised

a replacement from a 1936 Austin Ruby, filled its combustion chambers with

bronze and ground them to the required shape. He must have done something right

because the little Ulster's top speed increased to 87 mph! Bruce ran the Ulster for three years in all

and by the end of that time it was a completely different car to the restored

machine Les had given him. The springs were all changed, as were the wheels and

axles and the short tail became a long one. One thing never changed though: for

its entire life with the McLaren household, how quickly the car came to a halt

was limited by the speed with which the driver could go down the box. The

official brake system was always worse than useless but Bruce went along with

the Ettore Bugatti philosophy that brakes  are not essential in a racing car as

they only slow it down.

are not essential in a racing car as

they only slow it down.

In August 1955 he decided to sell the gallant little car for £280, a sum

which, with a borrowed £30, was turned into a Ford Ten Special and Bruce's

career was up and running. But he never forgot the little Ulster. In 1989 it was spotted in a museum in New

Zealand's South Island and McLaren bought and restored it.

RUSSELL TOPHAM